Eisenhower's Bureaucrats

How the federal government taught its managers to cut red tape.

For the federal bureaucracy, the 1940s through the 1960s are a nostalgic time. The era saw one spectacular achievement after another: from winning World War II, to building the interstate highway system, to landing on the moon. At its high point, trust in the federal government reached almost 80% in the 1950’s, as opposed to only 20% today.

Trust in the federal government has plummeted alongside the federal government’s ability to accomplish anything – which is no coincidence. Although government competence has changed for many reasons, there is one forgotten reason: after the second World War, the government was competent because it taught its managers to be competent.

During World War II, the poor management in the federal government was keenly felt. Although federal management had never been especially good, it reached a boiling point when it began noticeably impeding the war effort. The Bureau of the Budget (now OMB) responded by creating a new management unit tasked with training federal managers.

They termed their newly-developed management approach work simplification, which held that implementation and policy went hand-in-hand, and therefore managers had to be trained to streamline procedure in order to achieve policy goals. Moreover, the Bureau of the Budget felt that this viewpoint could be systematically taught to federal managers of average competence, and developed a training program to do so.

Work Simplification

During the war, the civilian agencies were incredibly short staffed due to the draft, so any procedural red tape or poor distribution of work created instant bottlenecks. Many of these bottlenecks directly impacted the war effort, as (for example) with slow approvals for important construction projects. The Bureau of the Budget therefore began an initiative to improve management around 1942.

They conducted user research with several agencies and eventually felt they had a management system that could scale, which they termed Work Simplification. They taught managers Work Simplification at training seminars, and also created guides and pamphlets to distribute across the government. I quote from one of their guides1 that sets out the problem, the audience, and their goal:

Thinking of this sort has been going on in the United States Bureau of the Budget for some time. It has culminated in the decision to make a concerted drive to capture the best available means for exposing and disposing of common management problems, set it forth in clear, simple language, and put it in the hands of those who can use it to best advantage. And who are they? They are the operating managers of government: middle management people and first line supervisors. […]

From the standpoint of the Bureau of the Budget, Work Simplification is a method of attacking the procedural problems of large organizations by equipping first line supervisors with the skill to analyze and improve procedures. It provides a way of tapping the great reservoir of unused practical knowledge represented by this group.

Their management agenda developed a training program for the managers closest to the ground, rather than (as is common today) focusing on top leadership. The guide elaborates on their approach and its value:

In this program, operating agency people who have been instructed in the plan train agency first-line supervisors to study and solve the basic problems of their own units. Therefore, improvements grow from the “grass roots”, and management obtains results which cannot be achieved in any other way. Supervisors are taught to gather relevant facts quickly, to organize them in simple chart form, and to interpret them properly. […]

However, the cycle is not complete when the supervisors have merely mastered the use of the techniques. Every supervisor in each training group should successfully apply the techniques to the work of his office and come up with an improvement which is good enough to be adopted and installed. This is an extremely important feature of the program. It immediately produces a dividend—a saving in time, money, and manpower—thereby earning continuing support from the top management of the agency concerned. Equally important, with a success story on his record each supervisor is stimulated to continue to apply these techniques to his work problems. In the long run, it is this continued application of the analytical approach which will produce the really big dividends in improved federal management.

There were several elements to Work Simplification, more than could be discussed in a single post. This post drills down into a single and quite narrow issue, namely how managers were trained in process charting to simplify the flow of paperwork through an agency.

Process charting

At a Work Simplification training seminar, managers would be taught to create several types of charts for analysis, one of which was the process chart. The chart would show the flow of an application (or other document) through an agency from start to finish. But the purpose was not understanding procedure for procedure’s sake. To continue quoting the guide:

The process chart is a device for tracing and highlighting work flow. To make such a chart it is first necessary to identify an office procedure involving a number of steps in sequence. Usually a form, a paper, a case or other office medium is selected to be followed through the several steps in processing it. In some cases it may be the steps performed by a single individual that are recorded. In either event the steps are recorded in order on a special form which is provided for the purpose. […]

THE PROCESS CHART shows you the “who”, “how”, and “when” of a whole work process and permits you to ask “why” about every step. And only by asking what is the purpose of every step can you find ways of simplifying procedure, getting rid of bottlenecks in your unit and smoothing out rough spots.

This approach addressed one of the most common frustrations with manager’s approach to paperwork: federal executives are routinely experts in how a process is done, but equally often neither they – nor anyone else – knows why each step is done. The training forced managers to think about the purpose of individual steps, and consider if the process as a whole achieved the desired outcome.

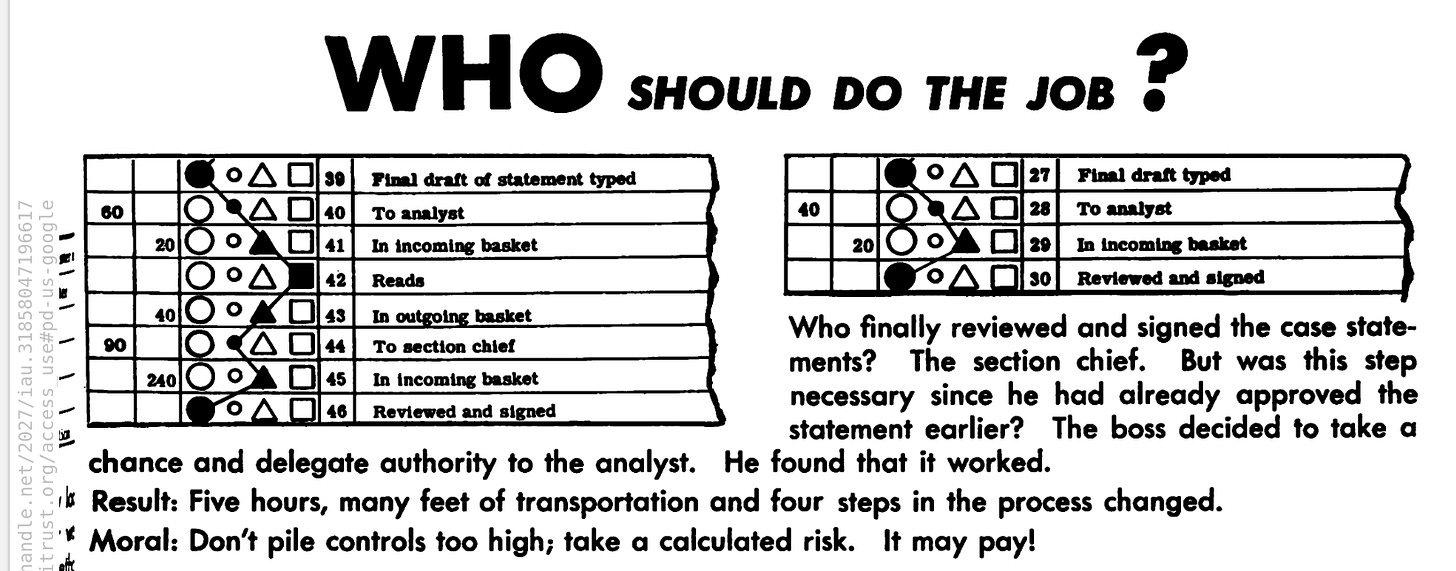

To be concrete, a process chart traced the lifecycle of a document and classified each step of its lifecycle into the following categories: (1) being created/changed, (2) being transported, (3) being stored awaiting further action, or (4) being checked/verified. Each of these categories was denoted by a particular (frankly unintuitive) symbol. A manager would transcribe the step-by-step lifecycle of a document and label each step with the appropriate symbol.

An example will likely make this clearer. The selection from the guide below shows both an example process chart and the sort of conclusion they might want managers to draw:

The purpose of understanding the process was to simplify the process. In particular, a government process often has individual safeguards that seem sensible in isolation, but that taken together waste a great deal of time in return for minimal gain. Managers were encouraged to consider the process as a whole and drop controls that failed to add value. Reformers today might well adopt as a motto “Don’t pile controls too high; take a calculated risk. It may pay!”

Lessons today

Although Work Simplification was developed during World War II, it was still the common approach for training federal managers into the 1960s. These were the stodgy managers of the Eisenhower era who oversaw the building of the interstate highway system, or the administration of the GI bill.

This is not how the federal government approaches management today. It would be, obviously, unreasonable to claim that earlier success was entirely due to training managers differently. But it clearly contributed – their methods explicitly aimed to solve issues that today’s processes aggravate.

In particular, the Bureau of the Budget’s work almost remarkably anticipated current conversations on government efficiency. Reformers note that the bureaucracy piles up layers of procedure without ever rethinking them – process charting taught managers to reduce procedural burden. Reformers note that government IT piles up layers of software from different eras, with nobody understanding how it fits together – process charting taught managers the start-to-finish viewpoint. Reformers note that bureaucrats rarely consider what it’s like to actually apply for benefits – once again, a failure that process charting aimed to correct.

Process charting is clearly not a perfect solution to any of these issues. But it is proof that the government can train bureaucrats to tackle these issues head-on!

The overall lessons of Work Simplification are even more important. Work Simplification’s success did not last forever, but it did last for several decades. And it achieved its success because the Bureau of the Budget created free training for low-level managers, while nobody else particularly cared.

So would-be bureaucratic streamliners today – proponents of product management thinking, agile IT development, or what have you – might imitate Eisenhower’s bureaucrats. Above all, they should prove that their proposals are a rational method that can be systematically taught to low-level managers, in order to put their “great reservoir of unused practical knowledge” to use.

Appendix: Do you want to simplify government, too?

This piece discusses only one part of the government’s training initiative (although it was the most important part). The training manual is called “Work Simplification as Exemplified by the Work Simplification Program of the U. S. Bureau of the Budget.”

The full manual is excellent, and well worth reading. It is online on Hathitrust. To read it, you have to be located in the US. To download it, you have to have an institutional subscription.

Alternative, I can send you a copy – it’s in the public domain. If you’d like a copy, message me on Substack, LinkedIn, email (khawickhorst@gmail.com), whatever. Just include your email address and the fact that you’d like the book.

All quotes and screenshots are from: Public Administration Service. “Work Simplification as Exemplified by the Work Simplification Program of the U. S. Bureau of the Budget.” R. R. DONNELLEY & SONS COMPANY, 1949.

The book is a compilation of the several guides to Work Simplification written by the Bureau of the Budget earlier in the 1940s.

This is an amazing post and everyone in federal government should read it right now.

This is stunning. To know there was a concerted and broad effort to retrain federal managers and workers in what today might be Lean or Agile or Six Sigma or Kanban or whatever is eye-opening in the extreme. And to learn it was fairly successful for decades is very encouraging.

Over the past several months I've been thinking about how to get our modern ideas -- largely developed by digital service teams -- into the hands (or minds) of all the managers or leaders in local government in particular. There's no concerted effort today to get these ideas out there. Digital service teams are trying to bring these continuous improvement ideas in the side door, but that's probably not enough to make a systemic improvement.

We probably need to somewhat standardize the models (like they did in the 1940s) and then build the skills, budgets, and focus required to roll the ideas out across every layer of government that can absorb it.