The High Tide of Reform: USDA Reorganization 1900-1960

A sketch of the history of government reform, as illustrated by USDA.

Government departments can be organized in many ways, and two important ways are subject-matter organization vs functional organization. In a previous post I laid out this distinction and claimed that subject-matter organization was more common in the past, whereas functional organization is more common today.

To illustrate these two types of organization, I contrasted the US Department of Agriculture in the early 1900s with USDA in the mid 1900s. Here I want to sketch out the history of this reorganization in greater detail. What were the steps to reorganizing this department, and when did these steps happen?

There were several major eras of reform. Functional agencies saw a slow growth up through the 1920s, and then grew rapidly during the 1930s. But the real changes were during WWII and immediately after, when the department was reformed along explicitly functional lines.

Reformers argued at length that – in their own words – functional reorganization was essential for greater efficiency. But their arguments were not strong ones. The entire history of USDA reorganization didn’t serve the needs of farmers or bureaucrats so much as it aimed to produce nicer looking org charts.

Before and After

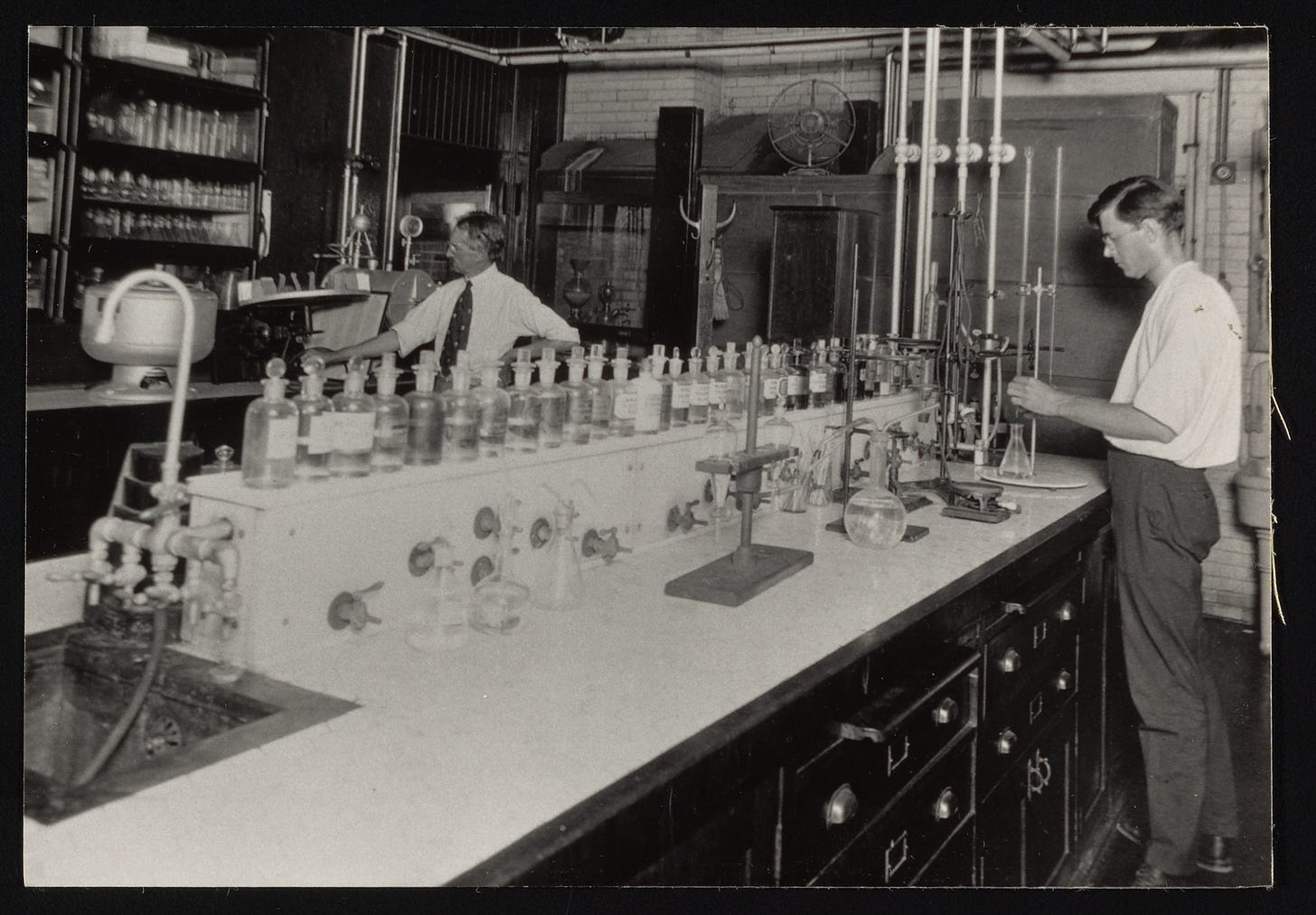

You might reasonably ask if this alleged trend towards functional organization actually existed. For prima facie evidence, compare how USDA was organized in 1905 to 1960.

In 19051, USDA’s org chart was very flat, with nearly everyone reporting directly to the secretary. The only other leadership was an assistant secretary and a solicitor, who were not in the chain of command.

Almost every bureau fits my definition of a subject-matter agency. There were two minor exceptions: first, one functional agency – the Office of Experiment Stations – described below. Second, there were also 5 administrative bureaus (not individually shown) which covered things such as disbursements, supplies, etc. On the whole though, the department was an almost textbook example of subject-matter organization.

In 19602, the org chart was far more complex. The secretary now had only five direct reports, who were assistant secretaries. The Assistant Secretary for administration oversaw the administrative bureaus, of which there were six (covering budgeting, personnel, etc).

A couple of trends stand out.

The organization of the department in 1960 is definitely by function. It is arranged into portfolios such as “federal-state relations” and “marketing and foreign agriculture.” These are broad statements of purpose rather than concrete subjects.

This wasn’t just a reshuffling where the same agencies were arranged under new functional assistant secretaries. Very few of the bureaus that existed in 1905 survived to 1960, so even the bureaus became functional agencies.

However, USDA still had a couple of subject-matter agencies. The Forest Service survived the reorganizations – and still exists today!

How did we get from the old to the new?

Functional agencies through the 1920s

At the turn of the 20th century, the department was organized into subject-matter bureaus. Most were founded in the 1890s or the first decade of the 1900s. For instance, the Bureau of Entomology was founded in 1894, whereas the Forest Service was founded in 1905. These bureaus combined every multiple functions relating to their subject: the Bureau of Entomology (say) researched insects, administered grants to educate farmers about insects, and condemned diseased crops. This was the most common approach for an agency at the time.

However, the government has never been exclusively organized in one way or the other. One of USDA’s longstanding functional agencies, shown in the 1905 org chart, was the Office of Experiment Stations, which coordinated the research of different bureaus. Each bureau had their own experimental stations for conducting research; this office attempted to maintain common standards of research quality and budgetary restraint. As described3 by the then-Secretary of Agriculture:

Although at the outset [the Office of Experiment Stations] had no authority over either the work or the funds of the stations, and even now exercises only a very limited control, it has nevertheless been an important factor in promoting their growth and development.

This was the first move towards centralization along functional lines, but it was a minor and sensible decision. In the 1910s, Congress created a similar agency for coordinating local outreach, the Extension Service. Up through the 1920s, functional agencies in the federal government were mainly loose coordinating bodies with little managerial control.

A far more significant development was the creation of the Bureau of Agricultural Economics in 1922. This bureau was given the previously-existing portfolios of crop statistics, farm management, and marketing. The department officials felt that these tasks should not be assigned on a crop-by-crop basis, with one saying4:

The lack of economic sensibility displayed by the marketing men [prior to the reorganization] was astounding at times. They had been chosen because they knew cotton or wheat or potatoes or oranges, and not because they knew markets and marketing.

This was a more strident reform, but certainly a defensible one. Nonetheless, combining all of these functions in a single bureau of economics illustrated the growing prestige of functional organizations.

Besides the foregoing, USDA also gained several regulatory authorities throughout the 1920s. These were mainly assigned to new agencies on a subject-matter basis; some examples were the Grain Futures Administration and the Packers and Stockyard Administration.

Throughout the 1920s, USDA was organized largely along subject-matter lines with a few exceptions. These exceptions were a small number of coordinating bodies and a research group. However, these agencies could be – and later were – used as means to centralize power in the secretary’s office through functional reorganization.

Centralizing science and planning in the 1930s

The Great Depression saw widespread enthusiasm for scientific planning. Throughout 1930s, Secretary Wallace began to reorganize USDA along functional lines. In particular, he began to centralize scientific research and economic planning.

The centralization of scientific research began with a memo5 in January 1935, which stated:

Project system. Each bureau and office of the Department shall supply the Office of the Secretary with project statements covering in detail the work under its jurisdiction. These statements shall be drawn up in accordance with the manual of instructions, as issued by the Department and as supplemented from time to time. They shall be kept current and shall be supplemented by annual and other reports as specified in the manual of instructions. Great care shall be taken to insure the accuracy of all data required by the project system, as this will form the basis of the Department’s program of work.

Before this, each bureau kept records of their research separately. The Uniform Project System, as it was named, imposed uniform standards across the entire department. All research projects now kept work in a standardized way. When created in 1935, the Uniform Project System was originally a coordinating body; it was located in the department of finance and mainly used to justify budgetary requests. Scientific research was now decidedly more centralized than before, but each agency still had its own research agenda.

Secretary Wallace also centralized economic planning through turning the Bureau of Agricultural Economics (BAE) into the planning agency of USDA. In 1938, BAE was made the “arm of the secretary”6 and tasked with planning long-run agricultural development.

The bureau was used to plan long-run agricultural use and to forecast what sort of crop yields and incomes farmers might expect under these plans. Nor was this merely idle theorizing: the bureau attempted to gain control over county-level land-use planning committees.

Setting aside the merits of planned vs unplanned developments, the crucial development was that USDA tasked an agency with planning per se. The Soil Conservation Service, for instance, had its own long-run planning to help counties prevent soil erosion. Counterfactually, USDA might have tasked all of its bureaus with long-run planning rather than creating a functional agency dedicated exclusively to planning. (And not coincidentally, the Soil Conservation Service’s hatred for BAE was legendary.)

Besides the foregoing, USDA began administering many insurance and subsidy programs. These were of great importance but are less relevant to this specific history. They would probably be classified as “functional” if they had to be classified.

Functional Reorganization as a Necessity: World War II

The major turning point in USDA organization was during World War II. In order to prosecute the war, FDR was granted extensive powers to reorganize the government under the War Powers Act.

In 1942, FDR promulgated Executive Order 9069, which substantially reorganized USDA. Overnight, the subject-matter bureaus were transformed into nearly the modern organization.

The executive order made several major consolidations. Agencies were consolidated into four main USDA administrations: the Agricultural Marketing Administration, the Bureau of Agricultural Economics, the Agricultural Conservation and Adjustment Administration, and the Agricultural Research Administration.

In particular, the Uniform Project System was now used to administer the Agricultural Research Administration. It had been created eight years ago to coordinate the scientific research of the department in the Secretary’s office. But what was then created for coordination was now used for control. Almost all bureaus were deprived of their own research agendas through this reorganization, with research being centered in this new administration.

This and other departmental reorganizations during WWII were based primarily on a practical need: the leadership of agencies was horrendously overworked. All of the experienced officials had been drafted into doing military staff work, so agency leaders worked with minimal assistance (and predominantly underqualified assistance at that). Most agency leaders needed to limit their number of direct reports in order to accomplish any work at all, so some sort of reorganization was their only option.

Functional reorganization was the dominant theory of the time, so departments were reworked into a small number of functional agencies. These were significant reforms, but they were based on necessity: the lack of personnel compelled reorganization, functional organization was the readily available idea, and so administrators turned to it.

The WWII USDA reorganization was the first thoroughgoing functional reorganization for that department, and perhaps in the entire federal government! But there were many more to come.

Functional Reorganizations as an Ideal: the Hoover Commission

Following the New Deal and World War II, the executive branch was sprawling and unmanageable. To clean it up, Congress established a reform commission whose members were nominated by both president Truman and Congress. This commission was formally named the Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government but is typically called the Hoover Commission after its chairman, the former president Herbert Hoover.

The commission created recommendations in two steps. First, a task force would study some issue (such as a specific department, or a cross-departmental issue such as budgeting). This task force would write a highly detailed report. In turn, the committee would consolidate the task force report into to a short commission report, which included numbered recommendations. The commission then transmitted its report with recommendations to Congress. The committee was not required to agree with its task forces, but typically did.

For the Department of Agriculture, both task force and committee were in absolute agreement about the need for functional reorganization. As the task force explained7:

To meet the present and prospective responsibilities of the Department of Agriculture, the committee proposes to group all activities in the Secretary’s Office and in six major functional administrations: Research, Extension, Agricultural Resources Conservation, Commodity Adjustment, Regulatory, and Agricultural Credit.

[…]

Only the Administrators of the six Administrations [and 3 minor officials] will report directly to the Secretary. Assignment of responsibilities of present organizations in the Department to appropriate bureaus in the six functional Administrations should eliminate duplication and overlapping and the Secretary will have for the first time the framework for an integrated organization.

The commission itself considered functional reorganization to be so important that they made it their first recommendation8:

Recommendation No. 1

In general, we recommend an extension of the functional organization of the department and a better grouping of activities related to the same major purpose.

The purpose is to secure more concentration in the responsibility of direction, elimination of overlap, conflict and waste, and further, to make possible the realization of broad policies in the Department.

These were the Hoover Commission’s recommendations, but recommendations are only recommendations. It took an executive action to put them into effect. Using the powers of the Reorganization Act of 1949, Eisenhower proposed reorganizing USDA per the Hoover Commission’s recommendations.

In 1953, Eisenhower promulgated Reorganization Plan No. 2 of 1953, which was accepted by Congress. The plan itself was minimalistic: it only gave Secretary of Agriculture general reorganization power and provided him with three assistant secretaries.

In other words, the Reorganization Plan per se could have been used to reorganize the department according to any scheme at all. But the intention of it was to enable a functional reorganization, which Eisenhower’s Secretary of Agriculture Benson carried out.

After Benson’s reorganization, the department’s org chart had become the org chart of 1960 that was shown above. (Although note that Benson did not follow the proposals of the Hoover task force reformers. Contrast the four actual assistant secretaries with the six proposed functional administrations.)

Summary: A Reformist Era

At the turn of the 20th century, USDA was organized into subject-matter bureaus. Functional organization was not yet popular; more than that, it was precluded by the limited records of the time. Secretaries simply didn’t know precisely what their bureaus were researching, so it was impossible for them to centralize scientific research. The early functional agencies – coordinating bodies that collected statistics – gave secretaries more visibility into what their departments were really doing.

The newfound legibility of the departments, in turn, made reorganization tempting. In USDA, the Bureau of Agricultural Economics and the Uniform Project system were originally created to collect uniform records and statistics – an entirely reasonable goal! They were not intended to supplant any existing agencies.

However, once Secretaries of Agriculture had access to this information, they couldn’t resist the urge to use these centralized records for the purpose of centralized control. After statistics made the state of agriculture more legible to them, they proposed long-run economic planning of agriculture. After the uniform project system made their department’s scientific research more legible, they placed all scientific research in a single centrally-controlled bureau.

The overall history of USDA was one of increasing legibility leading to functional reorganization. And the history of USDA is largely the history of other departments, too. Most of them saw their subject-matter agencies created in the late 1800s or early 1900s. From there, the history was:

In the 1920s and 1930s, a growing sense that the organization of the department was inadequate (or merely ugly). A small number of functional agencies were typically created during this time, often for the centralized collection of financial or statistical data.

Agencies were often temporarily reorganized along loosely functional lines during World War II. Frequently, the previously-existing functional agencies were transformed from coordinating bodies that collected statistics, into agencies that used these statistics to control the department.

The agencies were then thoroughly reorganized – sometime in the late 40s through early 60s – and thereby permanently locked into functional organization. Typically, but not always, these were reorganization plans due to the Hoover Commissions.

Fixing What Wasn’t Really Broken

How should we explain this era of reform? The mania for functional reorganization seemed to outstrip any real justification for it.

The key to understanding the reformers is “the span of control”, or the number of people who directly report to a manager. This is obviously a very important consideration, particularly in business, but in this era it was taken as an ideal that admitted no tradeoffs. In the early 20th C, it was interpreted very strictly to hold that every manager should have roughly five subordinates, who in turn should have roughly five subordinates, and so forth. The status of USDA in 1905 was far from this ideal – the Secretary had roughly 15 direct reports. According to the reformers’ beliefs, the agency needed to be consolidated, and they wanted a putatively scientific basis for such a consolidation.

The reformers wanted to consolidate activities into six business silos, and wanted all previously-existing activities to fall neatly into one silo or another. They needed, then, a seemingly-objective method for sorting these activities. Functional reorganization offered a seemingly clear answer: place all of the regulation in the first silo, all of the research in the second, and so forth. This would ultimately give the head of an organization a small number of direct reports who each considered a concept rather than a specific subject. This would yield, supposedly, an “integrated” organization that could consider the “broad policies”.

The arguments for functional reorganization never engaged with counterarguments, or even really acknowledged them. The goal was largely to create nicer looking org charts, as defined by the then-prevailing “best practices” of business.

The Department of Agriculture had little enough to show from this half-century of reform. USDA’s bureaus were strikingly less effective after these reorganizations: once one of the premier research institutes in the world, USDA’s research in the 50s and onward has been largely unremarkable. The rise of the farm lobby was probably inevitable, but administering all aid through one or two undersecretaries gave the farm lobby a single point of contact for handouts. Centralization was even immediately counterproductive to the New Dealer’s goals: a centralized planning agency gave conservatives a single target in USDA to (successfully) attack.

The contrast with the earlier subject-matter organization was striking. At the turn of the century, USDA’s bureaus were highly mission-oriented and had strong ties to state universities, farmers, and state regulators. This embeddedness gave them a great deal of autonomy.

But by midcentury, the department was wholly owned by its lobbyists. While it certainly isn’t proof, it is striking that an expert on USDA history identifies9 its transition “from autonomous to captured state agency” as happening in the early 1940s: precisely the time of the functional reorganizations.

In fact, there are few (if any) organizations that were improved by these functional reorganizations. This history largely remains to be told, although Eric Lofgren has ably discussed these reorganizations in the context of the military. Most of these reorganizations were surprisingly poorly reasoned. The Hoover Commission urged reorganization along functional lines, but their arguments – preventing waste and securing better organization – were rather weak and could apply to nearly any proposed reorganization.

In the end, the reorganizations had little to do with the needs of government, and a great deal to do with passing fads of management.

Yearbook of the United States Department of Agriculture for 1906. Appendix Organization of the Department of Agriculture. Page 453.

The initial year of 1905 is chosen because there were several minor reorganizations in the years 1900-1905, but the organization thereafter was fairly stable for the next couple of decades.

Directory of Organization and Field Activities of the Department of Agriculture 1960.

Here, the cutoff year of 1960 is chosen arbitrarily.

Report of the Secretary of Agriculture. United States, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1909. Pg 129.

Black, John D. "The Bureau of Agricultural Economics. The Years in between." Journal of Farm Economics 29, no. 4 (1947): 1029.

Magoon, CA, Neil Johnson, and Martha Seymour. “The Central Project Office in the Agricultural Research Administration,” November 1950.

Hardin, Charles M. “The Bureau of Agricultural Economics under Fire: A Study in Valuation Conflicts.” Journal of Farm Economics 28, no. 3 (August 1946): 638. https://doi.org/10.2307/1232500.

Agricultural Functions and Organization in the United States: A Report with Recommendations. Prepared for the Commission on Organization of the Executive Branch of the Government. 1948 pg xiv.

The Hoover Commission Report. XI Department of Agriculture pg 238.

Hooks, Gregory. “From an Autonomous to a Captured State Agency: The Decline of the New Deal in Agriculture.” American Sociological Review 55, no. 1 (February 1990): 29. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095701.