If you asked DC insiders to define red tape, they would point you to the Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA). This widely-loathed law regulates the process by which the government may request information from the public.

The PRA attempts to prevent government agencies from asking too many duplicative questions to the public. The Act applies if an agency wants to ask a question to more than ten people. If so, the agency must go through a lengthy approval process (normally taking many months), which involves 1) review by the staff at the President’s Office of Management and Budget, and 2) opportunity for public comment.

This requirement makes it practically impossible for agencies to conduct user research or ask the public if government programs are working. Absurdly enough, the public-comment requirement makes it mandatory to ask if the government ought to ask a question, while also making it difficult to actually go ask the question! The PRA is intended to prevent the government from harassing citizens, but in effect prevents government from improving its processes.

Others have ably made the case against the (perhaps comically-misnamed) PRA, resulting in some improvements to how OMB approves user research. And reformers are continuing to press the case – I’ve even heard rumors that there will be several other must-reads on PRA reform published today, coordinated by the Niskanen Center. Keep your eyes peeled for pieces by Marina Nitze, Jennifer Pahlka, and Alex Mechanick!

But even with all this work, another question remains to be answered. Excessive paperwork is a perennial issue, so how did the government approach this problem in the past?

In the mid-1940s, paperwork was a dire problem. Since the New Deal, government agencies had been created at a furious pace, with each new agency inventing its own approach to paperwork. As the war ended, the public was sick of the confusing and user-hostile paperwork that was imposed on it.

The federal government was determined to get this under control. As part of broader management reforms, the Bureau of the Budget invented an approach to reducing the burden of paperwork called forms control. They grappled with the same problem that we face today – was their approach any more popular than the PRA?

In fact, forms control was so good that even private businesses begged the federal government to teach them its approach.

Forms control

Forms control was an approach to managing office paperwork, including both forms that the public filled out and (unlike today) purely internal office paperwork. That is, it was a process for an agency to keep track of both the number and substance of every form whatsoever that it used.

The Bureau of the Budget had begun researching ways to manage paperwork during World War II, inquiring about the best practices of both businesses and government agencies. With this research, it produced a manual, Simplifying Procedures through Forms Control, which taught a new systematic method for applying these best practices. (All quotes and graphics in later sections are taken from this manual.)

The manual stated that forms control had four goals, which (paraphrased) were:1

Eliminating unnecessary forms.

Establishing a standardized design language for forms, thereby ensuring uniformity and simplicity.

Producing and distributing forms as economically as possible.

Using the process for creating and revising forms to address underlying problems of office organization and procedure.

To accomplish this, agencies designated a small centralized team to manage the entire agency’s paperwork. Other teams who wished to create a new form or alter an existing one would file a request with this team. From here, the (paraphrased) steps to apply forms control were:2

Recording the request to create or revise the form.

Analyzing the form’s purpose and its relation to internal office procedures.

Applying uniform design standards to the form.

Assigning an identification number to the form.

Approving a final specification for the form.

Planning how to store and distribute the resulting form.

Evaluating the effectiveness of the forms control program itself.

The manual went on to explain each step. The manual received an unusual honor for government office manuals: it was reviewed by an academic journal, which stated:

The bulletin Simplifying Procedures through Forms Control is very nearly a definitive work on the subject. Although it was originally prepared solely for the use of federal agencies, so many requests for it were received from business firms, state and municipal governments, and universities, that it has now been reprinted for wider distribution.3

Of course, being a bestseller among businesses was even more unusual of an honor. Why was forms control an inspiration to the private sector, when the PRA today is among the most dysfunctional government procedures? For a start, forms control was done at each individual agency, with the Bureau of the Budget mainly offering advice rather than mandates.

But most importantly, forms control was tied to both user experience and procedural improvement.

Better user experience

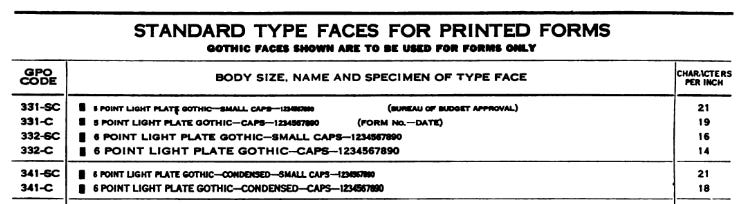

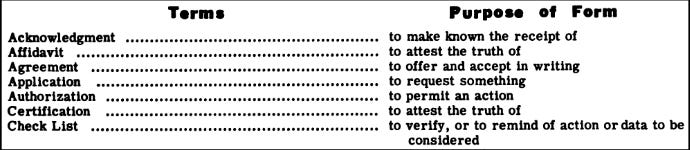

The Bureau focused on user experience through creating a standard design language for public forms. It included everything from approved fonts, to standardized sizes of paper, to a style manual for words and phrasing. The excerpts below are taken from the Bureau of the Budget manual:4

Fonts:

Style manual:

The Bureau then pushed government agencies to revise their forms to conform with this design language.

If you’ve ever noticed that federal government forms all look the same, it’s because the Bureau of the Budget pushed hard to standardize them in the 1940s. If you’ve never noticed, it’s because the Bureau of the Budget succeeded!

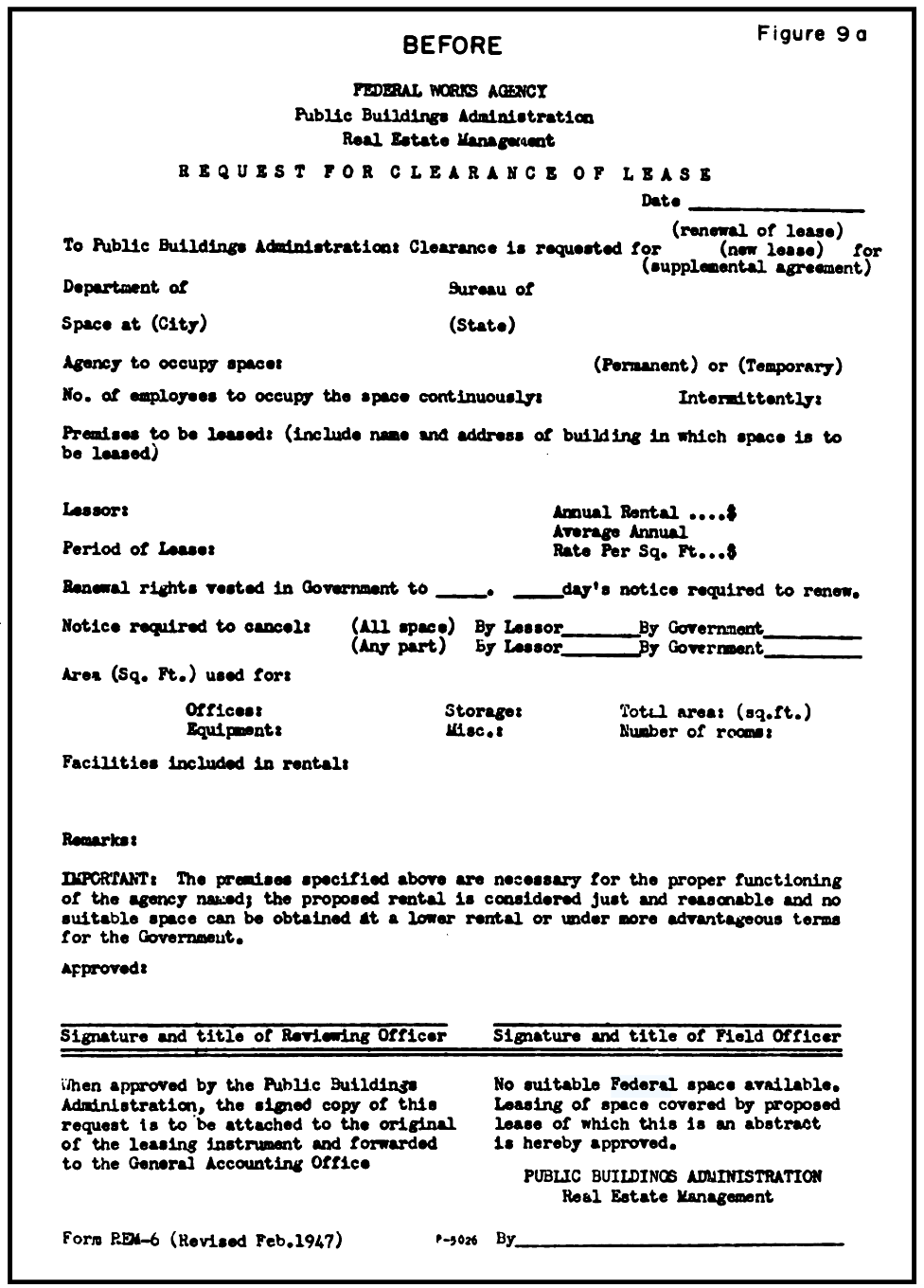

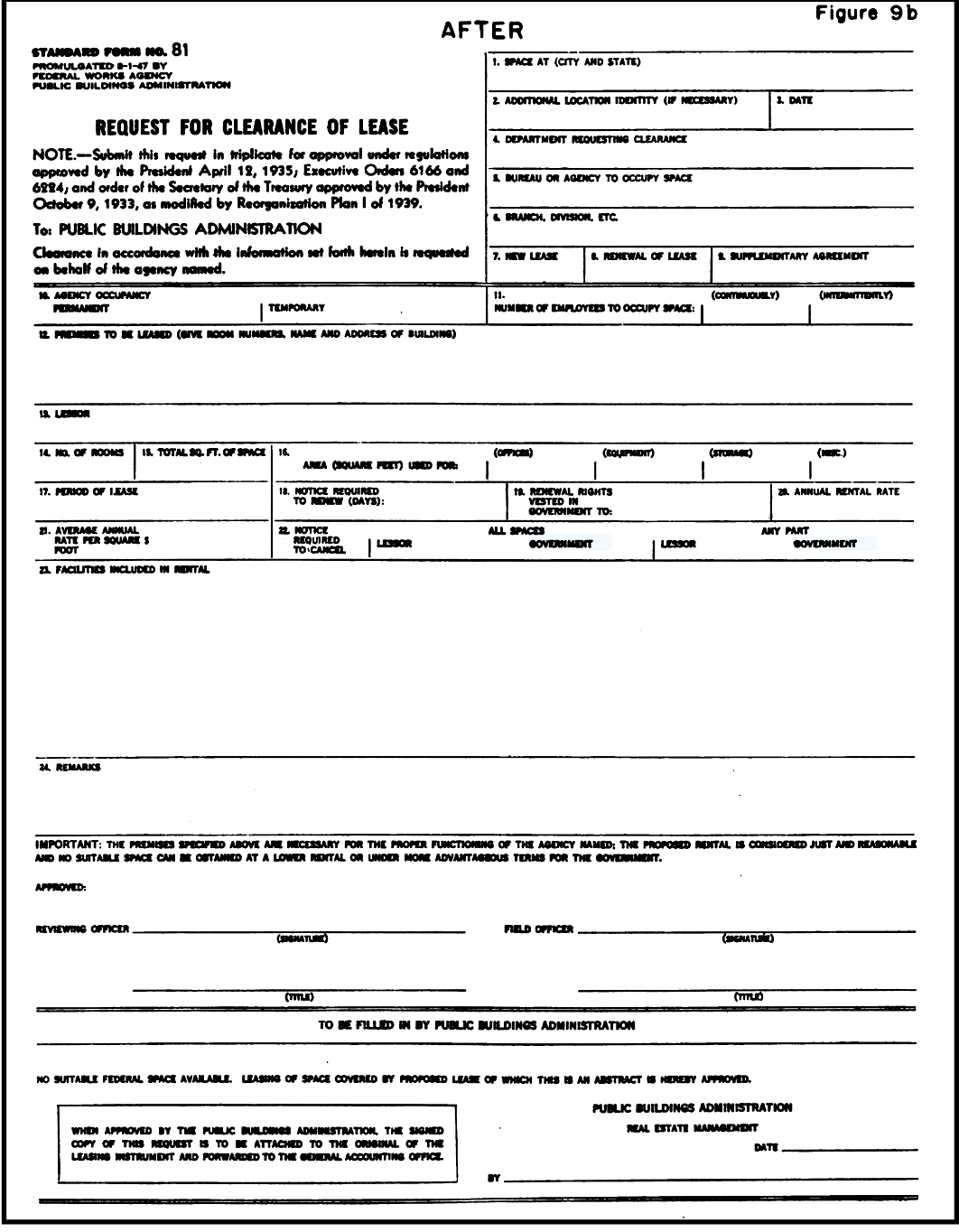

The guide shows a “before” and “after” of an actual government form to illustrate the design language being applied. The “before” form looks awful – e.g., it is difficult to see how many fields need to be filled out. The “after” looks like modern government paperwork.

Before:

And after:

How did the Bureau create this design language? While user research was primitive in the 1940s, the Bureau noted that their design language was the product of collaboration with both other government agencies and relevant experts from civil society (such as librarians and publishers).

Today, the PRA is administered by bureaucrats with little knowledge of design or user research – but in the 1940s, the government’s practices were cutting-edge.

Better procedure

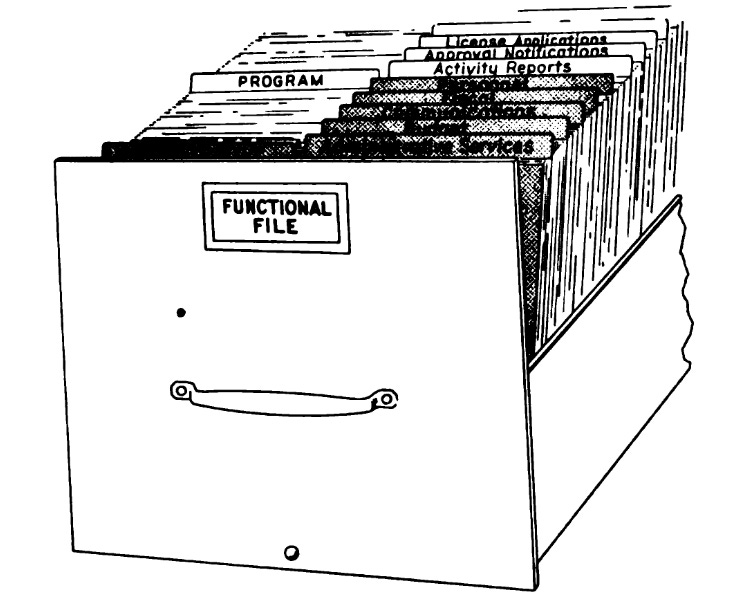

Forms control was also tied to procedural improvements. Agencies went through an approval process to create new forms, but also (unlike today) periodically reviewed existing forms in order to streamline and improve the way that an agency did business. To accomplish this, the agency would take a copy of every form and file it in a functional file.

The functional file (above) contained copies of forms grouped by major purposes. It might, for instance, have a group called farm aid: this might includes a form that the public filled out called application for aid and also include a form that only the agency filled out called review of aid application.

This file would be used to drive operational improvements. Managers were required to periodically look through related forms to see if duplicative forms might be combined. But more than this, the functional file showed public-facing paperwork side-by-side with purely internal paperwork. Managers were required to analyze ways to improve their office procedure: they might improve their use of the information that the public submitted, and conversely, they might stop asking for information that the agency did not actually intend to use.

Forms control was intended to serve the agency’s goals of streamlining its internal procedure in order to deliver high quality service, rather than be an end in itself. It was even supposed to speed up government rather than be red tape; indeed, the real purpose was to draw attention to the agency’s underlying procedures to improve faulty processes. The concluding section of the guide clearly explains this point:

In general, however, forms are a reflection of the work methods, operating procedures, and management know-how which give rise to their use. If an agency’s forms constitute a simple, orderly plan showing clear and related purposes, there is reason to believe that its personnel–knowing what they are doing and why–may be giving fairly efficient service. If, on the other hand, its forms constitute an unintelligible tangle of red tape, it is pretty safe to assume that its methods and procedures–its service to the public–are in much the same shape.

Therefore, great as may be the savings from eliminating unnecessary forms and getting all necessary ones properly related to existing procedures, forms control offers a still greater value as a means of detecting the need to treat the procedures themselves.

Paperwork: then and today

Forms control was part of the Bureau of the Budget’s broader set of management improvement initiatives, which went hand-in-hand to build up government competence. I have described two others: process charting and plain language. But what can we learn from forms control, specifically? Two things in particular: a better vision for government procedure, and a sense of how high reformers ought to aim.

First, it offers a better alternative to the Paperwork Reduction Act. Today, the PRA is administered by the Office of Management and Budget, or more specifically at its Office of Information and Regulatory Analysis. The small and inexpert team is a significant bottleneck on paperwork approvals that fails to add much value. More than that, the approach is purely a mandate. The PRA increases the burden on the government in hopes of indirectly benefiting the public.

Contrast this with the 1940s, where the forms control initiative invested in agencies, training them to minimize the burden on the public. This (mainly voluntary) guidance taught agencies to focus on user experience and operational improvement in order to better serve the public.

We could imagine a similar approach today. As a rough sketch, requests for information might be a chance to force collaboration between IT teams, data teams, and user experience experts. When an agency requests information from the public, it might review 1) the user experience the public faces in supplying the information, 2) the IT tools the agency uses to handle this information, and 3) how the requested information relates to other data the agency is already collecting. The US could, once again, view requests for information as a chance to improve the way that agencies do business. More broadly, we could abandon punitive approaches and figure out how to invest in agencies today.

Second, forms control shows us how much government can achieve when it buckles down. The approach of forms control was so successful that businesses and universities demanded that the government reprint a dry office manual. The Bureau of the Budget definitively answered the problems of the paper-based era and anticipated many issues of the digital era.

That is how high reformers ought to aim.

Appendix: Sources, and a question for readers

You can read the forms control manual on Google Books. It is excellent – note that I describe only two aspects of a broader program. My discussion leaves out many steps that are not directly relevant to UX or operations.

Sources:

Reilley, Ewing W., and Richard F. Neuschel. “Administrative Management Know-How.” Public Administration Review 10, no. 4 (1950): 291. https://doi.org/10.2307/972771.

US Bureau of the Budget. “Simplifying Procedures through Forms Control.” US Government Printing Office, June 1948.

Question for readers: When did your government improve its forms? This question applies both to foreign governments and to state and local government. My friend works at a state government and said they still used old-fashioned forms until the 1990s. (He claims that IRS-style fill-in-the-box forms were “an invention on par with the abacus, if not slightly more important.”)

I would love to know the foreign history and how the US compares.

Page 1.

Page 3.

Reilley Page 294.

Page 430-44.